Stimming is one of the most misunderstood aspects of neurodivergent experience. Teachers, parents, and caregivers witness it daily — rocking, flapping, humming, tapping, pacing — yet many still wonder: Why is my child doing this? Should I stop it? Is it harmful? Is it a sign of distress?

The truth is that stimming is not a problem to eliminate. It is a natural self-regulation strategy used by countless neurodivergent children — and even many neurotypical people — to cope with sensory input, emotional intensity, and daily stressors. It is a form of communication, a coping mechanism, a sensory-processing tool, and often a sign of how the child is navigating their environment.

This guide explores stimming in depth: what it is, why it happens, how to interpret it, how to distinguish it from behavioral escalation, and how to support children safely and respectfully. It combines research-based insights with practical strategies for both home and school settings.

The goal is to help adults shift from trying to stop stimming to trying to understand it.

1. What Stimming Really Is

Stimming (self-stimulatory behavior) refers to repetitive movements, sounds, or sensory actions used by a person to regulate their internal experience. While the word may sound clinical, the behavior itself is completely natural.

Examples include:

- rocking or swaying

- hand flapping

- pacing or running back and forth

- humming, whistling, or repeating phrases

- tapping fingers or objects

- staring at spinning objects

- rubbing fabrics or surfaces

- squeezing hands together

- smelling objects

- chewing on items

What makes stimming “different” in neurodivergent children is not the behavior itself, but the frequency, intensity, and purpose behind it.

For many children, stimming is not optional. It is essential.

2. Why Children Stim

Understanding the why behind the behavior is the foundation of all supportive responses.

2.1 Sensory Regulation

Many neurodivergent children have sensory systems that are either over-responsive, under-responsive, or inconsistent. Stimming helps them:

- block overwhelming sensory input

- increase needed sensory input

- make unpredictable environments feel more predictable

- reduce sensory stress

- maintain comfort and balance

For example:

- A child who feels overwhelmed by noise may hum to create predictable sound.

- A child who feels unbalanced may rock to find body rhythm.

- A child who is under-stimulated may jump repeatedly to increase input.

Educators often rely on sensory-focused training materials to better identify these patterns in students.

👉 https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Sensory-Processing-Disorder-Training-for-SPED-and-IEP-Teams-14865044

2.2 Emotional Regulation

Stimming is closely linked to emotions. It may appear during:

- stress

- excitement

- confusion

- joy

- frustration

- anticipation

- transitions

Examples:

- A child flaps hands when excited because the emotion is physically intense.

- A child rocks when anxious because the movement calms their nervous system.

- A child hums during challenging tasks to reduce cognitive pressure.

Stimming acts like an emotional “reset button” that helps the child manage what they are feeling.

2.3 Communication Without Words

When a child does not have the language to express emotions or sensory discomfort, stimming often becomes a form of communication.

Stimming may mean:

- “I need a break.”

- “This is too loud.”

- “This feels exciting.”

- “I don’t know what to do next.”

- “I’m stressed but I can’t say it.”

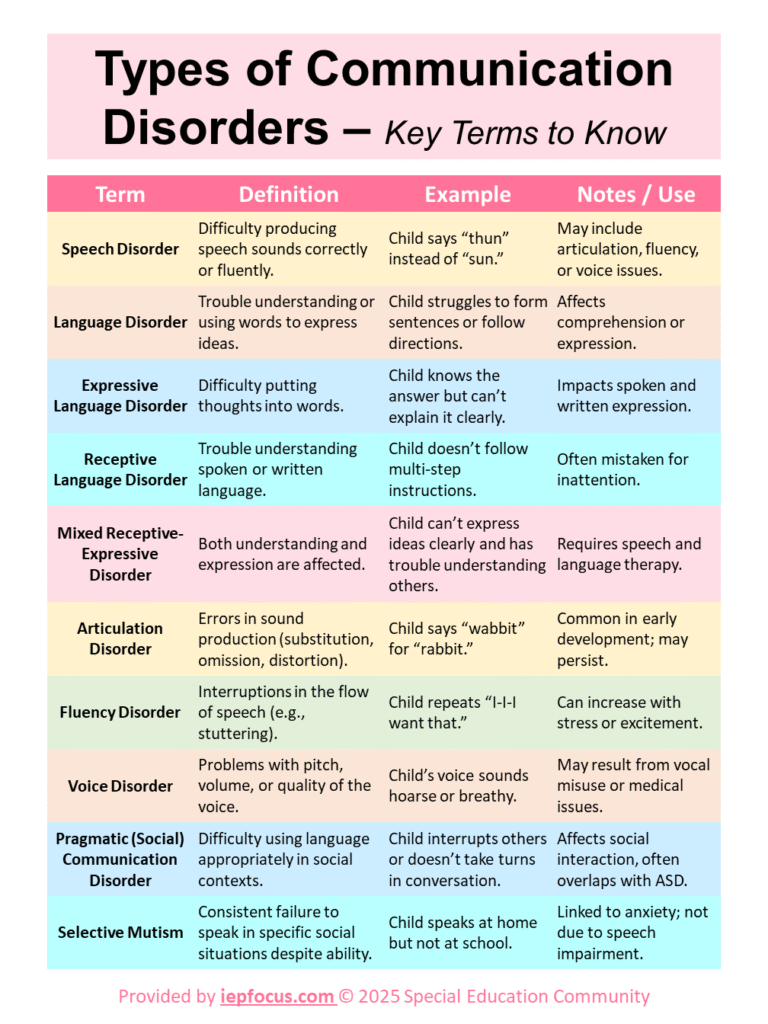

Many educators use communication reference charts to help teams avoid misinterpreting stimming as misbehavior.

👉 https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Types-of-Communication-Disorders-Educator-Reference-Chart-14866295

2.4 Attention and Cognitive Processing

For some children, movement supports thinking. This is why some adults walk while thinking, doodle during meetings, or tap their feet under the table.

Stimming can help a child:

- stay alert

- process information

- reduce mental overload

- organize thoughts

- remain engaged because movement releases tension

Suppressing stimming can actually reduce academic performance.

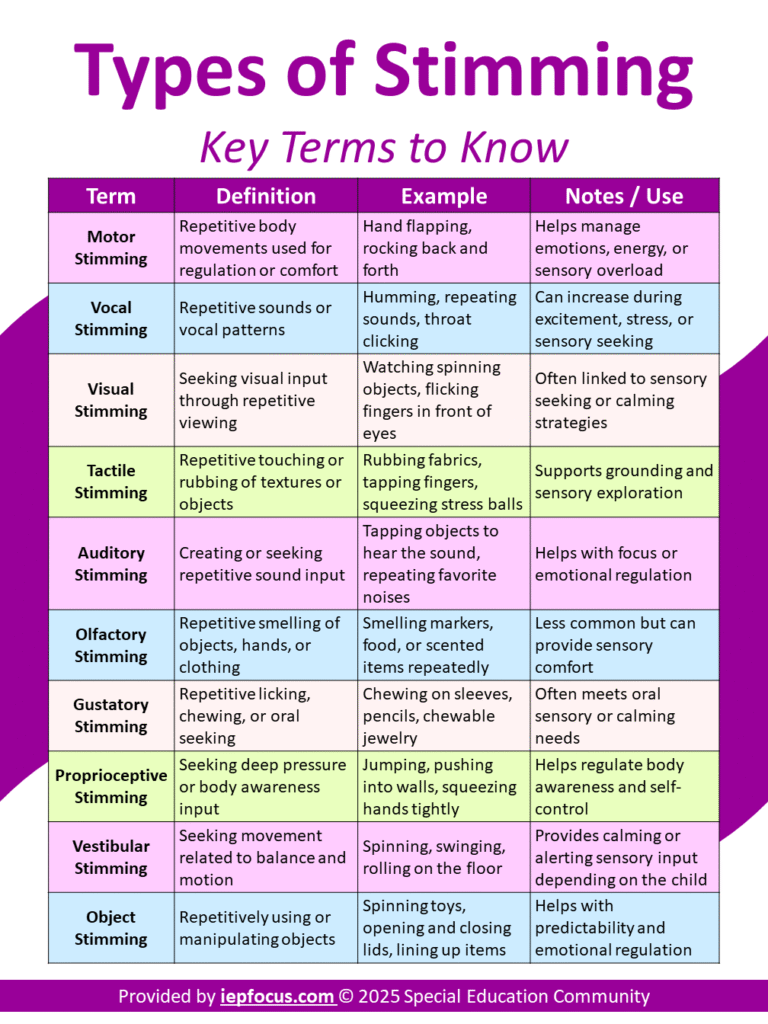

3. Types of Stimming (Explained in Depth)

Understanding the specific type of stimming provides insight into the child’s needs.

3.1 Motor Stimming (Movement-Based)

Includes:

- hand flapping

- rocking back and forth

- spinning

- pacing in patterns

- jumping or bouncing

- toe-walking

- repetitive arm movements

Motor stimming often relates to sensory regulation or emotional expression.

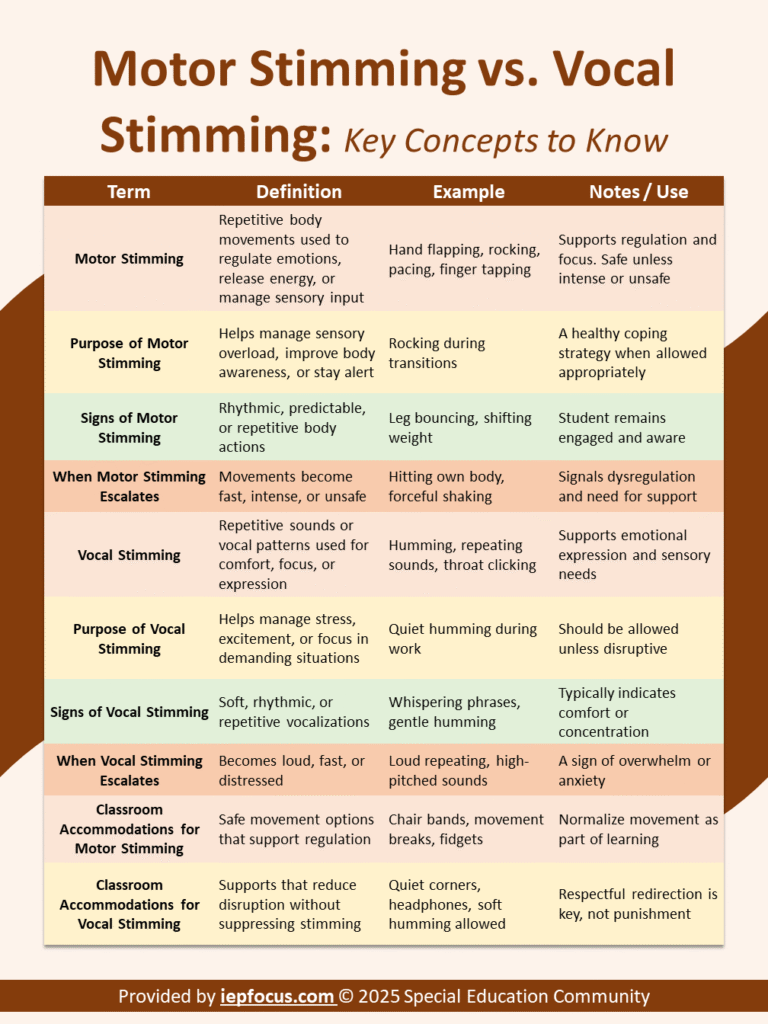

Many SPED teams use comparison charts that help staff distinguish motor stimming from vocal stimming when analyzing student behavior.

👉 https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Motor-Stimming-vs-Vocal-Stimming-Key-Concepts-to-Know-14871560

3.2 Vocal Stimming (Sound-Based)

Examples:

- humming

- repeating words or phrases

- making rhythmic sounds

- clicking the tongue

- whispering or scripting

- echolalia

Vocal stimming may reflect sensory needs, communication attempts, emotional intensity, or a desire for repetition.

3.3 Visual Stimming

Includes:

- watching spinning objects

- flicking fingers near the eyes

- staring at lights or reflections

- examining patterns

- lining up objects

- arranging items in precise ways

Visual stimming can help a child focus when overwhelmed by visual chaos or unpredictable environments.

3.4 Tactile Stimming

Involves touch, texture, and physical sensation:

- rubbing objects

- tapping surfaces

- squeezing modeling clay

- brushing textures

- running fingers along edges

Children often use tactile stimming to relax or feel grounded.

3.5 Proprioceptive Stimming

This involves deep body pressure and awareness:

- squeezing into tight spaces

- pressing against surfaces

- pushing or pulling objects

- lifting heavy items

- crashing into cushions

This type of stimming gives the body a strong sense of position and physical presence.

3.6 Vestibular Stimming

Movement related to balance and rhythm:

- swinging

- spinning

- jumping

- rocking

- sudden changes in movement

Using structured stimming guides helps educational teams differentiate between sensory needs and emotional needs.

👉 https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Types-of-Stimming-Key-Terms-to-Know-14864930

4. When Stimming Is Healthy and Helpful

Stimming is not inherently a problem. In fact, it often:

- prevents meltdowns

- reduces anxiety

- helps emotional recovery

- improves self-awareness

- enhances concentration

- supports sensory processing

- expresses joyful experiences

Children whose stimming is accepted tend to develop better self-regulation, higher self-esteem, and greater emotional resilience.

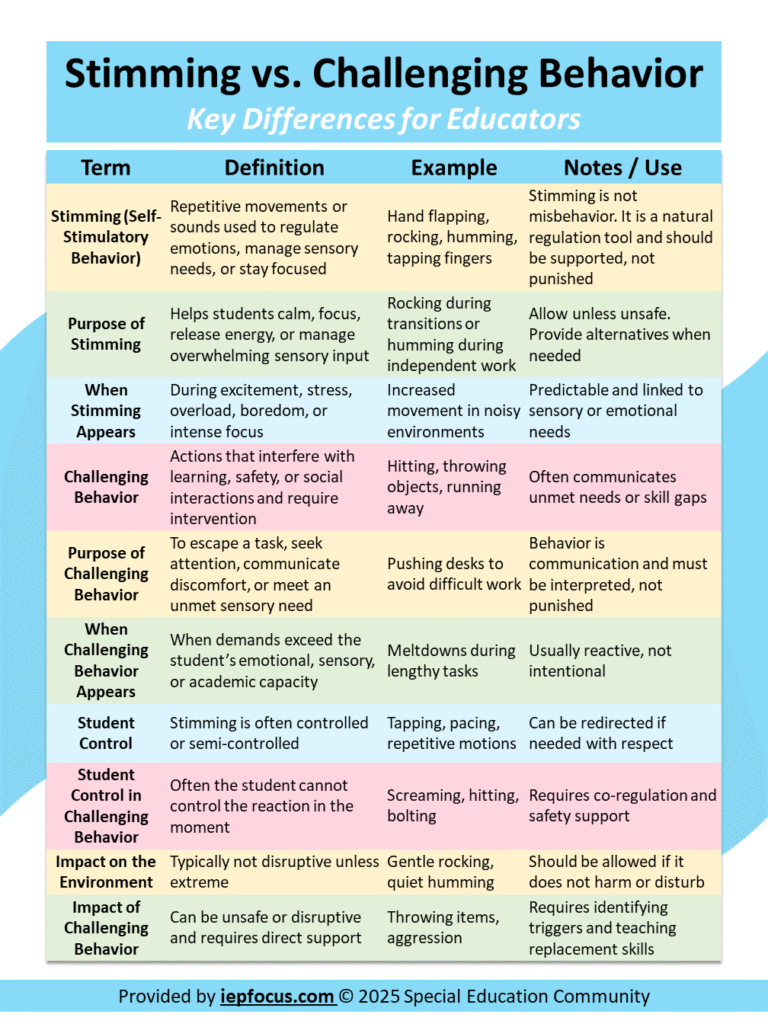

5. When Stimming May Signal Distress

Stimming becomes a concern only when it:

- causes self-injury (e.g., head banging, biting hands)

- harms others

- prevents essential functioning (e.g., cannot sit safely during meals)

- indicates overwhelming stress

- involves unsafe movement (running into danger, spinning near objects)

To differentiate sensory stimming from behavioral escalation, many professionals rely on quick-reference tools that break down observable differences.

👉 https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Stimming-vs-Challenging-Behavior-14866250

The focus should always be on safety, comfort, and understanding the underlying need.

6. What Parents and Teachers Should Do

6.1 Observe Before Acting

Before correcting the behavior, adults should ask:

- What happened right before the stimming started?

- Is there a sensory trigger?

- Is the child stressed, excited, confused, or tired?

- Is there a predictable pattern?

- Is the environment overwhelming?

Observation prevents misunderstanding.

6.2 Validate the Behavior

Validation reduces anxiety and strengthens trust.

Examples:

- “It’s okay, I see you’re trying to calm yourself.”

- “This helps you feel safe.”

- “I understand you need this right now.”

A calm adult creates a calm child.

6.3 Ensure Safety First

If stimming becomes unsafe:

- offer a safe alternative

- adjust the environment

- reduce sensory overload

- provide a break

- introduce physical supports like pillows or weighted blankets

6.4 Adapt the Surroundings

Simple changes can drastically reduce stress:

- lowering noise levels

- dimming harsh lights

- allowing movement breaks

- providing quiet corners

- using visual supports

- reducing clutter

The environment should support regulation, not trigger overload.

6.5 Build Predictable Routines

Predictability decreases anxiety and reduces distress-driven stimming.

Use:

- visual schedules

- timers

- countdown warnings

- first/then boards

- consistent transitions

Children feel calmer when they know what will happen next.

7. Safe and Helpful Stimming Alternatives

When children need safer options, adults can offer:

- fidget tools

- chewable sensory items

- weighted items

- sensory-friendly seating

- noise-canceling headphones

- calming jars

- tactile fabrics

- deep-pressure tools

- movement-based equipment

- mindfulness and breathing tools

Many SPED teams introduce parents to user-friendly stimming awareness tools to support home-school consistency.

👉 https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Stimming-Awareness-and-Training-for-Parents-and-Special-Education-Teachers-14864908

8. Creating Supportive Environments

8.1 Sensory-Informed Classrooms and Homes

Include:

- calm lighting

- soft seating

- sensory bins

- beanbags

- visual schedules

- accessible sensory corners

- rocking or swivel chairs

- quiet “escape” zones

A sensory-informed space is preventative, not reactive.

8.2 Teaching Children to Express Needs

Model statements like:

- “I need a break.”

- “I need quiet time.”

- “This sound is too much for me.”

- “I want to move.”

- “I need my fidget.”

Self-advocacy supports independence, especially during puberty and adolescence.

8.3 Collaboration Between Home and School

Effective support requires consistency:

- share observations

- share calming strategies

- communicate triggers

- discuss preferred stimming tools

- align responses across environments

Children thrive when adults work together.

9. Realistic Scenarios and Professional Responses

Scenario 1 – Noise Overload in Class

A child begins rocking and covering their ears during a loud group activity.

The teacher quietly guides the child to a calm corner and offers noise-reducing headphones.

Outcome: the child returns regulated and ready to participate.

Scenario 2 – Happy Stimming at Home

A child flaps hands and jumps while excited about a TV show.

The parent responds with acceptance and continues the routine.

Outcome: the child associates joy with safety, not shame.

Scenario 3 – Stimming During Transitions

A child hits their head during classroom transitions.

The team identifies transitions as overwhelming and introduces:

- visual transition cards

- predictable countdowns

- break cards

- deep-pressure alternatives

Outcome: reduced distress and safer regulation.

Conclusion

Stimming is not a flaw, a misbehavior, or a sign of failure. It is a meaningful, functional, and often essential strategy that helps neurodivergent children navigate a world that can feel noisy, bright, confusing, or emotionally intense.

Parents and SPED teachers who understand the purpose behind stimming become powerful allies in a child’s journey toward self-regulation, confidence, and independence. By responding with empathy, adapting the environment, and supporting sensory needs, adults help children thrive — not despite their stimming, but often because of it.

Stimming is not the problem.

Misunderstanding it is.

When we understand stimming, we understand the child.