Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental condition characterized by inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. Historically, ADHD has been more frequently identified in boys, leading to a perception that it is a “boys’ disorder.” In reality, girls and women also experience ADHD, often with different manifestations and challenges. In childhood, boys are about three times more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than girls. By adulthood, prevalence rates between men and women become more equal, as many females remain undiagnosed until later in life. Understanding the gender-based differences in ADHD is crucial for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and support in educational settings. This report examines recent scientific findings on how ADHD presents differently in girls versus boys, focusing on diagnostic challenges, behavioral traits, treatment differences, and educational impact across the lifespan.

Diagnostic Challenges

Underdiagnosis in Girls: One of the biggest challenges is that ADHD in girls often goes unrecognized in early years. Clinical studies have traditionally reported a male-to-female diagnosis ratio around 4:1, but community-based surveys show a much smaller gap (approximately 2.4:1), suggesting many girls with ADHD symptoms are never formally diagnosed. Large-scale data indicate that girls who exhibit clear ADHD symptoms are significantly more likely than boys to remain undiagnosed, pointing to a lack of recognition of the disorder in females. Often, girls with ADHD do not display the “classic” disruptive hyperactive behaviors seen in boys, so their symptoms (e.g. quiet inattention or internal restlessness) may fly under the radar. Many girls are first identified only in adolescence or adulthood, when academic or life demands exceed their coping strategies.

Biases and Symptom Presentation: Research has uncovered several factors contributing to the underdiagnosis of ADHD in females. Clinicians and educators have long held biases – for example, a historical belief that ADHD is rare in girls (and even rarer in adult women). Diagnostic criteria were originally developed and normed predominantly on male samples, aligning more with male symptom patterns. Consequently, girls’ symptoms, which often skew toward inattention and daydreaming rather than hyperactivity, may be overlooked or misinterpreted. Parents and teachers are also less likely to rate girls as having ADHD even when their behavior is similar to boys’, due to the absence of overt disruptive behavior. Girls tend to use compensatory strategies to mask their difficulties – for instance, a girl might meticulously organize her schoolwork or behave extra quietly to hide her inattention, thus avoiding drawing attention to her struggles. These coping mechanisms, combined with the higher prevalence of internalizing symptoms (like anxiety or depression) in ADHD females, can lead professionals to misattribute a girl’s difficulties to anxiety, mood issues, or personality traits rather than ADHD. Furthermore, the DSM-5 diagnostic framework requires symptoms to be present before age 12, which might exclude girls whose impairments become marked during puberty or adolescence. Emerging evidence even suggests that adjusting diagnostic thresholds might be warranted – one recent study found that requiring only 4 symptoms (instead of the standard 6) for females would capture many girls with significant impairment, without changing the criteria for males. In sum, a combination of stereotyped expectations, subtler symptom profiles, and criteria not fully attuned to female presentations all contribute to diagnostic challenges for girls with ADHD.

Behavioral Traits

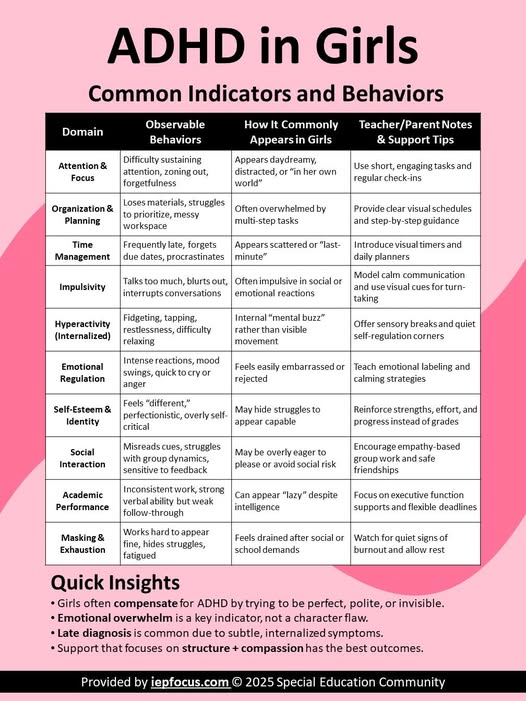

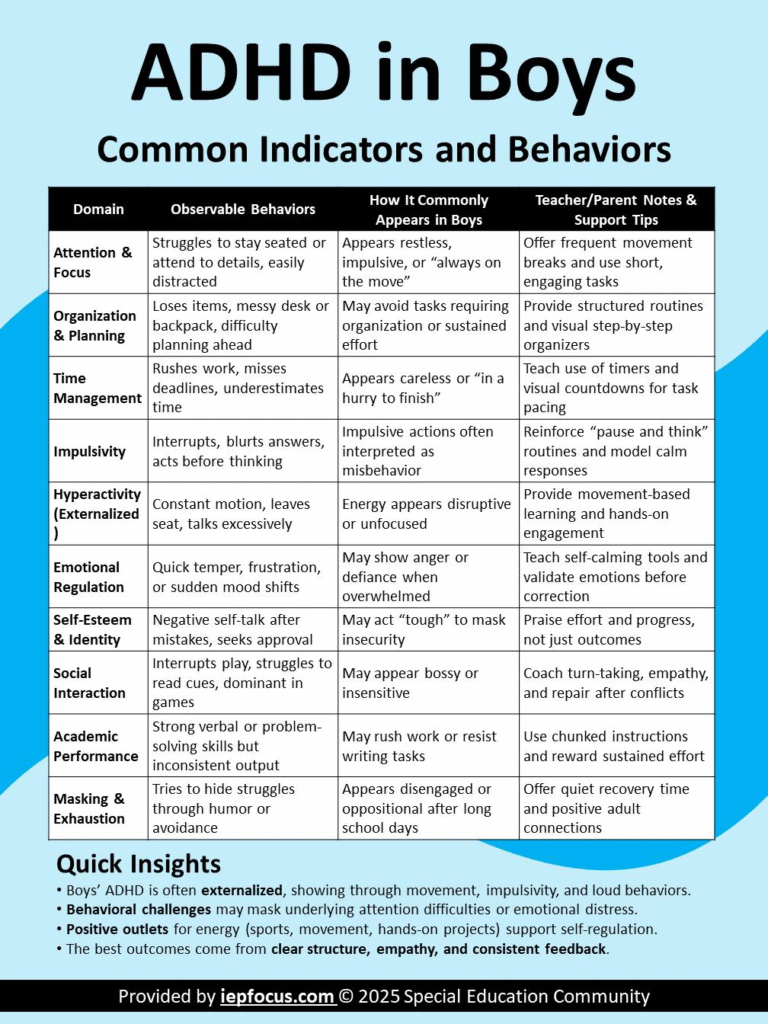

Symptom Expression: ADHD manifests with a different emphasis in girls versus boys. Boys with ADHD more often show externalizing behaviors – they tend to be hyperactive, impulsive, and physically disruptive, which makes their ADHD visible in classrooms and at home. Girls with ADHD, on the other hand, frequently exhibit more internalizing features. They are more likely to have the inattentive subtype, characterized by disorganization, forgetfulness, difficulty sustaining attention, and quietly daydreaming. While boys might be constantly out of their seats or blurting out answers, a girl with ADHD might sit in the back appearing withdrawn or “spacey,” struggling to focus on the lesson. Importantly, girls can and do experience hyperactivity and impulsivity, but these behaviors often manifest in less obvious ways. For example, rather than running around the classroom, a hyperactive girl may be excessively talkative or “hyper-verbal,” chatting and fidgeting in her seat. This form of hyperactivity is more socially oriented and thus can be misinterpreted as mere sociability or excitability rather than a symptom of ADHD.

Social and Emotional Differences: Aside from core symptoms, there are gender differences in the social and emotional profile of ADHD. Girls with ADHD often have as much trouble with peer relationships as boys do, and some studies suggest their peer difficulties can be even more pronounced. They may be socially isolated or struggle to maintain friendships, sometimes due to impulsive speech, forgetfulness of social plans, or oversensitivity to social cues. In terms of aggression or disruptive behavior, boys with ADHD are more prone to physical aggression and oppositional conduct, whereas girls (when they do have conduct issues) might engage in more relational aggression (e.g. gossiping, exclusion of peers). Still, the overall rates of overt conduct problems tend to be lower in ADHD girls than in boys, contributing to the perception that girls “behave better.” Emotionally, females with ADHD often experience greater emotional dysregulation – intense mood swings, frustration, and internalized stress – which can be mistaken for or co-occur with mood and anxiety disorders. By adolescence, many girls with ADHD report significant levels of anxiety or low self-esteem, partly as a reaction to chronic difficulties in organization and attention that go unrecognized. Boys with ADHD also face self-esteem and emotional issues, but girls are more likely to internalize their problems (e.g. feeling guilt or shame about not meeting expectations) rather than acting out. This internalizing tendency in girls contributes to higher rates of comorbid conditions like anxiety, depression, or eating disorders among females with ADHD. In fact, teenage girls with ADHD have been found at higher risk for problems such as eating disorders, self-harm, and even suicidal thoughts or attempts compared to their male counterparts with ADHD. On the flip side, boys with ADHD have higher rates of externalizing comorbidities like oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder. These differing co-existing problems further color the behavior of each gender: an ADHD boy might end up in the principal’s office for fighting or defiance, whereas an ADHD girl might quietly struggle with anxiety or an eating issue that teachers could miss entirely.

Cognitive and Developmental Trajectories: There is evidence that developmental timing of ADHD symptoms varies by sex. Longitudinal research indicates that girls with ADHD often experience a peak in symptom severity (particularly impulsivity) in early adolescence, around middle school years, whereas boys tend to have more severe symptoms in earlier childhood. In other words, some girls “grow into” noticeable hyperactive-impulsive symptoms as teens – a time when hormonal changes and increasing life demands occur – even if they showed fewer problems in elementary school. Boys, conversely, often present with high activity and impulsivity in early childhood, and some show improvement or adaptation by adolescence. Inattention symptoms in girls and boys also follow different patterns: one study found that inattention tends to remain more stable (and problematic) for girls over time, whereas for boys with severe childhood inattention there was more improvement as they grew older. Such differences mean that the window for catching and addressing ADHD can differ by gender. Additionally, neurocognitive studies suggest subtle differences in executive functioning: for example, girls with ADHD may have relatively greater difficulties with planning and organizing (especially compared to girls without ADHD), whereas boys with ADHD show larger deficits in impulse control (inhibition) relative to boys without ADHD. Still, both genders experience executive function challenges; the differences are in degree and specific profile. The bottom line is that ADHD’s core impairments – inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity – affect both boys and girls, but the outward behaviors and secondary effects (social problems, emotional issues, etc.) often differ. These behavioral nuances are key to recognizing ADHD in girls, who might otherwise be dismissed as simply “daydreamy, sensitive, or chatty” rather than identified as children in need of support.

Treatment Differences

Diagnosis and Treatment Gap: Because girls are less frequently diagnosed in childhood, they often miss out on early interventions that many boys receive. Studies show that even after diagnosis, girls with ADHD are prescribed medication less often than boys. This may reflect a continuing bias – perhaps the misconception that girls’ ADHD is less severe – or practical issues such as girls getting diagnosed later when they or their families might be more hesitant about medication. Consequently, many girls go longer without treatment, which can worsen long-term outcomes. Once in treatment, however, there are no separate clinical guidelines by sex; standard evidence-based treatments for ADHD (stimulant medications, behavioral therapy, or a combination) are recommended for both genders. That said, emerging research suggests certain nuances in how girls and boys respond to treatment.

Medication Efficacy and Adherence: Stimulant medications (like methylphenidate or amphetamines) are effective for managing core ADHD symptoms in both boys and girls. However, gender-specific patterns have been observed in treatment response and adherence. Girls with ADHD often report that medication helps them with emotional regulation and social functioning, domains in which they may have greater difficulties than boys. For instance, a girl might find that her stimulant medication not only improves her concentration but also makes her less overwhelmed by emotions and better able to interact with peers – benefits that address the internalized aspects of her ADHD. Boys, who tend to have more overt hyperactive symptoms, often show dramatic improvements in externalizing behaviors (sitting still, reducing impulsive acts) on stimulants, which is readily noticed by teachers and parents. One difference, however, is that females appear more likely to discontinue medication due to side effects or perceived lack of efficacy. Adolescent girls, for example, might stop taking stimulants because of appetite suppression (which can be particularly concerning amid body image pressures) or mood side effects, or simply because they feel the medication isn’t addressing all their problems. Research has found that adherence challenges are higher in females with ADHD than in males, necessitating a more personalized approach to keep girls engaged in treatment. Improving adherence for girls may involve choosing treatments with fewer side effects, providing education about what improvements to expect, and addressing any stigma or family beliefs around ADHD medication.

Treatment Tailoring: Given the differences in symptom profile, comorbidities, and physiology, a one-size-fits-all treatment may not be optimal. Clinicians are beginning to emphasize gender-sensitive treatment plans. For example, girls and women with ADHD often have co-occurring anxiety or depression, so they may benefit more from non-stimulant medications (like atomoxetine or guanfacine) which can treat ADHD without potentially exacerbating anxiety. Evidence suggests females sometimes respond more favorably to these non-stimulant options, especially when mood symptoms are present. Boys, in contrast, generally respond very well to stimulants for their hyperactive/impulsive behavior, and are often less affected by certain side effects. Hormonal differences are another consideration: fluctuations in estrogen levels can influence ADHD symptoms and medication effectiveness in females. For instance, some adolescent girls experience a worsening of concentration and mood symptoms premenstrually, which might prompt adjustments in their treatment plan. Similarly, adult women may notice ADHD symptoms worsening during menopause (when estrogen drops), potentially reducing stimulant efficacy. Though research in this area is still growing, clinicians are advised to monitor how hormonal changes affect their female patients’ ADHD and adjust treatments accordingly. Beyond medication, behavioral and psychosocial interventions are crucial for all children with ADHD, but certain emphases differ by gender. Social skills training or therapy addressing self-esteem may be especially beneficial for girls, who often grapple with social acceptance and internalized criticism. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and organizational coaching can help adolescents and adult women with ADHD manage time, work, and home responsibilities, building on the fact that females often have had to develop their own coping strategies. Ultimately, a multimodal approach – combining medication (when appropriate) with behavioral therapy, school accommodations, and psychoeducation – tends to yield the best outcomes for both genders. The key is ensuring girls are not left behind in accessing these treatments and that any unique needs (like treating coexistent anxiety or adjusting for hormonal effects) are addressed.

Educational Impact

Academic Performance and Challenges: ADHD can significantly affect academic achievement, but the impact may differ for girls and boys due to their distinct symptom patterns and the likelihood of intervention. Boys with ADHD, being more frequently identified early, often receive classroom support, individualized education plans, or medication during their school years – interventions that can help mitigate academic problems. Girls with ADHD, especially those who are undiagnosed or diagnosed late, might go through school without such support, despite struggling. This hidden struggle can translate into lower academic performance and lost educational opportunities for girls. Indeed, untreated ADHD in females has been linked to poorer academic achievement and lower rates of educational attainment over time. Many girls with ADHD expend great effort to compensate in school – for example, spending hours each night re-reading materials they couldn’t focus on in class, or relying on friends’ notes – which can lead to exhaustion and burnout. Despite such efforts, they may receive lower grades than their intellectual ability would predict, particularly in subjects requiring sustained attention and organization.

Research indicates some subject-specific impacts and differences. In mathematics, for instance, inattentive symptoms (common in girls) are detrimental to performance: one longitudinal study found inattention correlated with weaker math achievement in both sexes. Notably, in that study, hyperactivity had a small positive correlation with math performance, possibly reflecting that mildly hyperactive students engaged more with classwork, but inattention consistently harmed math learning. Over time, boys with ADHD showed slight improvement in the impact of inattention on math (perhaps as hyperactive behaviors were addressed or as they matured), but for girls the negative impact of inattention on math stayed equally strong, resulting in a persistent performance gap. Large-scale data from schoolchildren have reported that girls with ADHD tend to be more impaired in numeracy (math skills) than boys with ADHD. This could be because their concentration difficulties often remain unremediated and compound over years. On the other hand, in language arts, there is some evidence of girls with ADHD faring relatively better than boys with ADHD. Girls generally develop language skills earlier, which might help them compensate in reading and verbal tasks. In one observational study, girls with ADHD outperformed boys with ADHD in reading fluency and comprehension, even though inattention was strongly linked to reading problems in both genders. Boys with high inattentiveness had especially poor reading comprehension, whereas girls with equivalent inattention showed less severe reading deficits, possibly due to their verbal skill advantage. However, when girls with ADHD do have additional problems like hyperactivity or conduct issues, those can significantly undermine their academic skills. For example, girls with ADHD who also exhibited high levels of externalizing (disruptive) behavior were found to have notably worse reading comprehension than girls without such behaviors, an effect not seen in boys. This suggests that while girls on average might mask academic difficulties longer, those who have the full gamut of ADHD symptoms (inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive) can experience a compounded academic toll.

School Experience and Motivation: Beyond test scores and grades, ADHD impacts a student’s overall school experience, and here again girls may suffer in unique ways. Girls with undiagnosed ADHD often receive feedback that they are “not working up to potential” or are careless, which can erode their self-confidence. They may become quiet and withdrawn in class to avoid drawing attention to what they perceive as personal failings, or conversely, some become class clowns in an effort to mask academic struggles. Boys with ADHD, who are more often externally unruly, tend to get direct disciplinary action, whereas girls might get overlooked until their academic performance drops sharply. One study on predominantly inattentive ADHD (ADHD-I) in early adolescents found that the drop in school motivation, academic expectations, and achievement was significantly larger in girls with ADHD-I compared to boys with the same subtype. This implies that the subtle challenges of ADHD-I (like difficulty following through on assignments, losing materials, etc.) may disproportionately dampen girls’ engagement with school. Possibly, societal expectations on girls to be organized and academically competent play a role – when girls struggle, they might internalize it as a personal flaw and thus become demotivated. Girls with ADHD also report feeling misunderstood by teachers more often. Because they’ve masked symptoms, a sudden decline in performance or an emotional outburst might be met with less empathy (“She’s just being dramatic” or “lazy”) compared to the more consistent pattern seen in boys with ADHD.

Over the long term, the educational impact of unaddressed ADHD in girls can be severe. Many capable girls with ADHD may end up underperforming in high school, missing college opportunities, or selecting less demanding career paths not for lack of talent, but due to cumulative effects of unmanaged ADHD. It is also noteworthy that ADHD-related educational impairments carry into adulthood. Women with ADHD are less likely to complete higher education and tend to have lower occupational achievement, especially if their condition was never treated in youth. This underscores the importance of early identification and support. When girls with ADHD receive appropriate interventions – tutoring, classroom accommodations (like extra time or help with organization), therapy to build study and coping skills, and medication when needed – they can thrive academically just as well as boys with ADHD. The key is ensuring that their difficulties are taken seriously and addressed, rather than overlooked due to a quieter demeanor or societal biases about gender.

Conclusion

Growing evidence makes it clear that ADHD manifests differently in girls and boys, necessitating a tailored approach in both diagnosis and management. Girls with ADHD face unique diagnostic challenges: their symptoms are often quieter and more internal, leading to underrecognition and delayed diagnoses. This delay has a ripple effect, contributing to untreated symptoms that impair academic progress and self-esteem. Behaviorally, while boys more frequently exhibit classic hyperactivity and impulsivity, girls typically grapple with inattentiveness and subtle hyperactivity (like excessive talkativeness), as well as higher rates of internal emotional turmoil. These differences mean that parents, teachers, and clinicians must keep a keen eye out for the less obvious signs of ADHD in girls. On the treatment front, one size does not fit all. There is a need for gender-sensitive treatment plans – for instance, addressing comorbid anxiety in girls, considering non-stimulant medications or therapy for emotional regulation, and providing support around life stages (such as adolescence or menopause) that can exacerbate symptoms. Encouragingly, when properly diagnosed and treated, girls and women respond well and can lead successful lives with ADHD, just as boys and men can.

From an educational standpoint, schools and families should be aware that ADHD can undermine a girl’s academic trajectory just as much as a boy’s, even if it causes less obvious disruption in the classroom. Academic accommodations and interventions should be granted based on need, not on outward behavior intensity. Moreover, improving awareness is crucial: teacher training and public health education can help dispel the myth that ADHD is only a boy’s issue, reducing stigma for females who seek help. Finally, ongoing research is needed to continue unraveling the complexities of ADHD across genders. Females have been underrepresented in ADHD research for decades, but recent studies are closing this gap. By pursuing inclusive, sex-specific research and updating clinical practices accordingly, the field is moving toward more equitable identification and care. In summary, recognizing how ADHD manifests differently in girls versus boys enables a more nuanced and effective approach – one that ensures all individuals with ADHD, regardless of gender, get the support they need to succeed in school and beyond.

Sources:

- Hinshaw, S. P., et al. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry (2021) – Review on underrepresentation of girls and women with ADHDfrontiersin.org.

- Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2025) – Systematic review of sex differences in ADHD among youth frontiersin.org.

- Duke Center for Girls & Women with ADHD (2025) – “ADHD in Girls and Women: Key Facts” (compilation of research findings) psychiatry.duke.edu.

- Amiri, D. et al., Middle East Current Psychiatry (2025) – Narrative review on gender disparities in ADHD treatment outcomes mecp.springeropen.com.

- Silva, D. et al. (2020s) – Various studies on academic performance differences in ADHD by sex frontiersin.org.

- Young et al., BMC Psychiatry (2020) – Consensus statement on females with ADHD across the lifespan psychiatry.duke.edu.